Transition Layer Surfacing Welding Wire for Roller Presses

The roller press is a widely used, high-efficiency and energy-saving grinding equipment, especially suitable for the pre-grinding of cement clinker. It is also effective for grinding limestone, blast furnace slag, lime sandstone, raw coal, gypsum, quartz sand, iron ore and other materials. The main feature of the roller press is to extrude materials under high pressure ranging from 50 to 300 MPa to achieve the purpose of comminution. The surface of the roller press roll is subjected to high-stress abrasive wear under extremely harsh working conditions, and wear is inevitable after a period of use. In addition, due to foreign objects such as iron blocks or improper operation leading to excessively small roll gap, spalling or low-cycle fatigue spalling may occur on the roller press roll sleeve.

The roll body material is forged steel 34CrNiMoA or 42CrMo steel, which is very expensive. In most cases, replacement is not feasible, and on-site repair is the only option. Therefore, effective protection must be applied to the surface of the extrusion roll during the manufacturing of the roller press. At present, surfacing wear-resistant materials on the surface of the extrusion roll is recognized as the most effective and convenient method.

There is a significant gap in strength between the high-hardness roll surface wear-resistant layer and the roll body material. Directly surfacing the wear-resistant layer on the roll body is prone to large-area spalling problems. Therefore, it is necessary to design surfacing materials with different strength levels between the roll surface wear-resistant surfacing layer and the roll body material to ensure the reliability of surfacing. In addition to ensuring the wear resistance of the roll surface pattern layer, the fatigue spalling resistance of the transition layer must also be guaranteed. Therefore, the transition layer surfacing material for the roller press must have good plasticity and toughness.

The roll sleeve material is generally medium-carbon alloy steel, taking 42CrMo as an example, which is quenched and tempered after forging. 42CrMo steel has high strength, high hardenability, good toughness, small deformation during quenching, and high creep strength and rupture strength at high temperatures. It is used to manufacture forgings that require higher strength and larger quenched and tempered cross-sections than 35CrMo steel. The comprehensive carbon equivalent of 42CrMo is 0.78%. Due to its high carbon equivalent, it has a strong hardening tendency and is a relatively difficult-to-weld material. Elements such as Mn and Mo in its composition increase the susceptibility to white spots and are prone to delayed cracking. When the contents of P and S are also high, hot cracking is likely to occur. To prevent hot cracking, the selected welding wire should have low C, P and S contents and high Mn content to enhance desulfurization. The microstructure after quenching and tempering is tempered sorbite maintaining martensitic orientation.

The T-series welding wires of Shandong Xinyuan Botong are Fe-Cr-C series high-chromium cast iron flux-cored welding wires, characterized by self-shielding, minimal slag or slag-free properties without adding any slag-forming agents. As a pioneer in open-arc surfacing in China, these welding wires have a high market share and are widely recognized by the industry. Their alloy wear resistance can maintain good hardness and wear resistance even at high temperatures above 350℃. The hardness of the wear-resistant working layer after surfacing is as high as HRC 60 or more, with a large number of microcracks.

If wear-resistant flux-cored welding wires are directly surfaced on the base metal, due to the large difference in melting temperature between the deposited metal of the wear-resistant layer and the base metal, melting is asynchronous. The metal with low melting point melts prematurely, causing sagging or lack of fusion with the metal with high melting point. In addition, the metal with high melting point solidifies and shrinks earlier, which will cause stress on the low melting point metal that is still in a partially solidified and weak state, possibly leading to cracks.

In addition, the linear expansion coefficients of the two microstructures differ significantly. Inconsistent cooling shrinkage between them will cause large internal surfacing stress, which can lead to surfacing cracks in severe cases. Thermal stress will be generated during high-temperature operation. This thermal stress cannot be eliminated (post-weld heat treatment can eliminate welding residual stress, but thermal stress is generated during service).

According to the above working conditions, this condition no longer belongs to the welding of dissimilar steels, such as welding between F (ferrite), M (martensite) and A (austenite) dissimilar steels. This working condition should be the welding of medium-carbon alloy steel and wear-resistant high-chromium white cast iron. The specially developed transition layer material must have high toughness and crack-stopping performance, and the surfacing metal must have excellent crack resistance and impact toughness. It should effectively prevent the welding cracks and fatigue cracks on the roll surface from extending and developing towards the roll body, thus effectively protecting the roll body from damage.

The isolation surfacing method is used between the medium-carbon alloy steel and the wear-resistant surfacing layer. A metal with a linear expansion coefficient between the two metals is selected as the filler metal for the transition layer to reduce the thermal stress caused by the difference in linear expansion coefficients. Cost issues also need to be considered to solve the above problems. Different from the chemical industry and boiler pressure vessel industry, the isolation layer has a large thickness. If conventional austenitic stainless steel (18-8) welding materials are used for surfacing the isolation layer, the cost will be very high. In addition, the toughness and plasticity of the fusion zone with the wear-resistant surfacing layer need to be considered. Carbon "migration" occurs in this layer, resulting in carburized and decarburized transition zones. The sudden change in hardness in these zones will cause adverse effects, thus easily leading to fatigue failure in these areas.

However, due to the scarcity of nickel resources and the recent sharp increase in its price, it is necessary to replace nickel with other elements to reduce costs. The effect of manganese on austenite is similar to that of nickel. Therefore, manganese can be used instead of nickel to produce low-cost austenitic stainless steel welding materials.

Carbon is a strong austenite-forming element, with an austenite-forming capacity 30 times that of nickel. However, it cannot be added to corrosion-resistant stainless steel because it will cause sensitization corrosion and subsequent intergranular corrosion problems after welding. In this working condition, the carbon content of the wear-resistant flux-cored welding wire after surfacing is more than 4%. Excessively high carbon content will increase the hardness and brittleness of the weld, which is not conducive to toughness.

To overcome the intergranular corrosion of chromium-nickel stainless steel such as 18-8, the carbon content of the steel is generally reduced to below 0.03%, or elements with stronger affinity for carbon than chromium (such as titanium or niobium) are added to prevent the formation of chromium carbides. In this working condition, where high hardness and wear resistance are the main requirements, the carbon content of the steel is increased to meet the requirements of hardness and wear resistance.

Both manganese and nickel are austenite-forming elements, meaning they can form an infinitely miscible solid solution (austenite) with iron. However, the role of manganese is not to form austenite, but to reduce the critical quenching rate of steel, increase the stability of austenite during cooling, inhibit the decomposition of austenite, and allow the austenite formed at high temperatures to be retained at room temperature. Manganese has little effect on improving the corrosion resistance of steel. Therefore, in this working condition where corrosion resistance is not required, it is completely feasible to use Mn instead of Ni to obtain a single-phase austenite structure. At the same time, Mn has a greater solid solution strengthening effect than Ni, which can improve the performance of the steel. In addition, the formed MnS can replace FeS, which can prevent hot cracking and is thus beneficial to welding. Manganese can also offset the adverse effects of some harmful elements and is an element that reduces the susceptibility to solidification cracking.

Nitrogen is also a strong austenite-forming element, with an austenite-forming capacity 30 times that of nickel. However, it is a gas, so only a limited amount of nitrogen can be added to avoid porosity problems. It can be seen from the nickel equivalent formula that adding manganese is not very effective in forming austenite. But adding manganese can dissolve more nitrogen into the stainless steel, and nitrogen is a very strong austenite-forming element. Nitrogen with a content of 0.25% has an austenite-forming capacity equivalent to 7.5% nickel. However, the manganese content should not be too high, otherwise, it is easy to cause coarse grains during solidification and high-temperature service, increasing the brittleness of the material. Therefore, excessive amounts of manganese and nitrogen cannot be added.

In the case of no nickel or low nickel content, to form a 100% austenite structure, the addition of chromium can be reduced with reference to the Schaeffler diagram. Although this leads to a decrease in corrosion resistance, it is feasible under working conditions with only impact, wear and no corrosion or slight corrosion. With the chromium content reduced and the carbon content high, to prevent the formation of chromium carbides, a certain amount of strong carbide-forming elements such as niobium and titanium can be added.

In the 200-series stainless steel, sufficient manganese and nitrogen are used to replace nickel to form a 100% austenite structure. The lower the nickel content, the higher the required amounts of manganese and nitrogen. For example, type 201 stainless steel contains only 4.5% nickel and 0.25% nitrogen. According to the nickel equivalent formula, this nitrogen content has an austenite-forming capacity equivalent to 7.5% nickel, so a 100% austenite structure can also be formed. This is the formation principle of 200-series stainless steel.

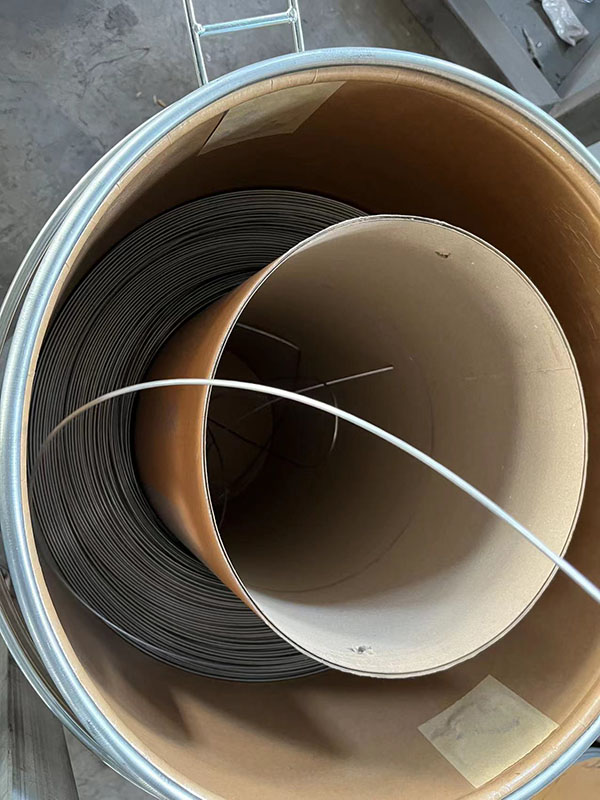

Based on the above ideas, our company has successfully developed T96 special isolation surfacing flux-cored welding wire through formula experiments. The hardness after surfacing is 180-220 HB. It is a welded metal alloy with corrosion resistance, impact resistance and high-pressure stress resistance.

While meeting the performance requirements of the roll sleeve transition layer, the cost is reduced by 45% compared with 18-8 chromium-nickel austenitic stainless steel. It not only saves valuable nickel resources but also reduces costs. T96 flux-cored welding wire is not only suitable for the new manufacturing and repair of roller press roll sleeves but also for the new manufacturing and repair of cast steel vertical mill roll sleeves. It can also be used for surfacing workpieces subjected to high impact or rotating loads. It is suitable for transition layer welding in hardfacing and repair welding of manganese steel wear-resistant parts.